by Michell Spoden

All these crime shows on television invite public’s interest in the field of forensics. An interview with a forensic artist, Lisa Bailey, a full-time forensic artist, offers a special view into the world that television often misses.

Michell: Please explain to our viewers what a Forensic Artist is?

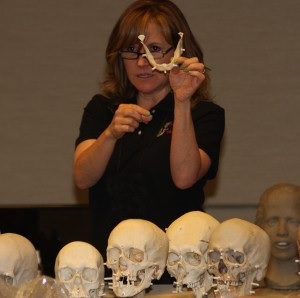

Lisa Bailey: A forensic artist, despite the name, doesn’t create art. We work to create forensic facial images for use in law enforcement investigations, such as composite sketches, fugitive age progressions, or depictions based on unidentified remains. Most forensic artists do the work as a collateral duty within their agency, so they are a detective or patrol officer first, and then do forensic artist assignments on an “as needed” basis.

Michell: In what ways is this art form used?

Lisa Bailey: The primary purpose of forensic art is to provide leads for investigators in the identification of suspects, unidentified remains or the apprehension of fugitives. For instance, when a victim says that they can remember a suspect’s face, we work with them to create the best likeness possible, in the hopes that someone will recognize that individual and call in a lead to police. This is one field where the public’s input to solving cases is vital.

Michell: Are there historical roots to this art form?

Lisa Bailey: The prevailing wisdom is that it goes back to the days of the Wild West, when “WANTED” posters appeared with a sketch of what the bad guy looked; sort of the first composite drawing. Early attempts at facial approximation, building a face onto an unidentified human skull, go back to the late 1800s.

Michell: When did you notice that forensic art became more of a source to rely on?

Lisa Bailey: I think the internet, and even social media, has had a huge impact in how forensic art can be useful in a law enforcement investigation. Twenty years ago, a sketch shown on the evening news in one city would stay right there, in that city alone. Now, people are sharing composite images or facial approximations on Facebook, linking to stories they see on the news, emailing each other “have you seen this person?” Now, someone in California can call in a lead for a case they saw in Florida just minutes before. It’s really opened the doors to getting our images out where they can be useful.

Michell: Did you have to go to school for this? If so where did you graduate from?

Lisa Bailey: Forensic art is a very unusual line of work. Although there are commercial classes and workshops, there is no degree program. Even if there were, most police agencies wouldn’t care about it or require it. As long as the artist can do the work, and help produce leads for investigators, that’s really all that matters.

Most artists start work at agencies in their primary role (detective, patrol officer, crime scene tech, etc.) with no thought to forensic art. Then later, they get interested in the field, take a class, and learn much more “on the job” as they go along. Sometimes there will be a senior artist that can help them along the way, but forensic art can be a lonely endeavor. We all have to help each other.

Michell: I noticed that you have worked for a police department before. How did you use your abilities there?

Lisa Bailey: I’m actually at a law enforcement agency now, and do every aspect of forensic art: composites, age progressions, post mortems, sculptures from unidentified skulls, digital retouching, and more. I came from a graphics-and-illustration background, and fell into the forensic side of work. That’s how most forensic artists got into this field—it wasn’t a conscious decision; forensic art found them.

Michell: I personally was a victim of a crime and it was never solved. One reason was that I could not see the persons face but I can distinct fully remember certain things. Have you been able to help victims of crimes to identify their perpetrator by using your gift?

Lisa Bailey: Interviewing a witness or a victim of crime is actually a learned skill. We used a process called “cognitive interviewing”, where instead of a limited “Q&A” format, the person is encouraged to talk about what they remember, beginning with a free flow of information. Sometimes a person will open up more to an artist, and just the process of creating an image can spur more memories. Any tidbit of new information can help the investigation and produce more leads.

Michell: One YouTube video that is on your Facebook page gave an example of what a forensic artist did with the dove company. He was helping women find their own beauty. Recently I reflected on an article about a very beautiful actress who came out to tell everyone that she never really felt beautiful. Do you think in today’s world there are many women who do not think they are beautiful? Do you think that this could be a form of therapy to help women find and appreciate their own beauty?

Lisa Bailey: I think most women are much too hard on themselves. I think that’s more age-related, actually. As I’ve gotten older, I care less about the surface things, and more about what I can DO, what I can accomplish. By the way, I know a number of artists who have gotten some freelance work from that video; people asking for a drawing to see what they “really” look like! It’s incredible how that one video has hit a nerve with people.

Michell: Do you believe art is a spiritual thing?

Lisa Bailey: Yes. But, it doesn’t have to be, to be considered art. I think commercial illustration is vastly under-rated and appreciated. Two of my favorite artists—JC Leyendecker, NC Wyeth—were considered by the established art field at the time to be “just” illustrators. Now, their work is viewed to be as rich and compelling as anything you’ll find in a museum.

Michell: What are the most typical questions people ask you?

Lisa Bailey: Most people either want to know: how did I become a forensic artist, or, how can they become one! Other questions are related to the “nuts and bolts’ of the job, like how do we know how to sculpt facial features from a skull, or how do we know how to age progress a picture of a person.

Michell: What is your favorite charity?

Lisa Bailey: Anything related to helping animals.

Michell: What are some of your future goals?

Lisa Bailey: I’ve been working on a book for a while now. My primary goal is to educate people about what forensic is, and what it is capable of doing. I also want to help anyone that wants to be a forensic artist to learn how to go about it, with real, concrete advice. I want more artists in this field, and am doing all that I can to make that happen!

About the Interviewer

Michell Spoden is the author of Stricken Yet Crowned and is also pursuing a transitional housing project for woman with an agricultural aspect. She has a degree in Business Science Administration and is finishing her bachelor’s in Project Management.